Tracing the Sun

by afatpurplefig

I’m feeling pretty good when I wake, due mostly to the prospect of soon spending some time alone. My roommate is cool, clever and kind, but I would be fibbing if I didn’t admit I’m thrilled that the NCP students are moving to their uni accommodation.

It will be a gift just to have the place to myself.

Magnus is always first in the hotel lobby for our meeting time. I am always in the top five.

(Perhaps I am reliable, after all.)

Our group has effectively been halved. I might have missed the exuberance of our youngsters, if I wasn’t so relieved that we will be less unwieldy in public places. It will be nice not to feel personally responsible for inconveniencing the locals.

Our compact bus heads to Xúzhōu Bówùguǎn, situated at the foot of Yúnlóng Shān. We take another of what feels like hundreds of group photos.

博物馆 (bówùguǎn) = museum (broad object building)

When Frances, our tour guide in Sūzhōu, learned of our destination, she exclaimed, ‘Why are you going to Xúzhōu?‘ as though it were the last place on earth she anticipated. I think this might be why I expected the museum to be small…or possibly quaint.

Xúzhōu Bówùguǎn is far from quaint.

It is packed to the rafters, both with visitors and extraordinary exhibits. I particularly like the seals, which were used by nobles as signatures. They were often found buried with their owners, which gives them a whole other dimension.

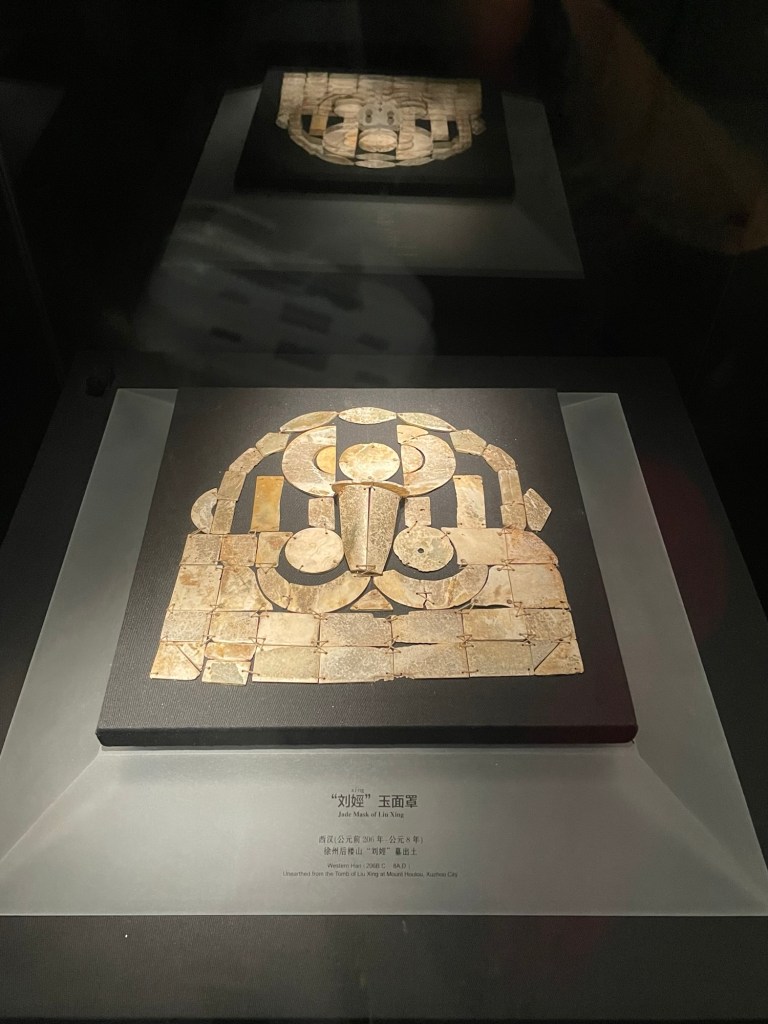

The jade is exquisite, shaped into all manner of objects – weapons, figures, masks. Benjamin asks us to guess the use of what looks like a rectangular box, its jade green emblazoned with gold.

‘Cigarette holder?‘ I proffer.

‘Pillow,’ he replies.

I manage the substantial crowds by sneaking an AirPod into one ear and hiding it with my hair, like my students. The soothing tones of JJ Lin are a lyrical security blanket.

A small boy is delighted when I smile at him. A few minutes later, he taps me on the arm, holding a phone that reads, ‘Where are you from?‘ I sure do love a question I can answer.

‘Wǒ shì Àodàlìyà rén,’ I reply.

He gifts us small green packets. ‘Fragrant stomach,’ Conall translates.

澳大利亚人 (Àodàlìyà rén) = Australian person (phonetic transliteration)

My favourite displays (and that of many others, given how hard they are to get close to) is the jade burial suits. I am particularly enthralled with the image of the cave-side location where one was discovered. The body had long since dissolved, leaving a mess of jade squares flat to the earth.

(I send the images to Lucy.)

After lunch, we head to the Guīshān Hàn Mù. It is the joint burial site of Liú Zhù, the sixth king of the State of Chu during the Western Han dynasty, who reigned from 128-116 BC. The tomb has two burial chambers: one for Liú Zhù and one for his consort, whose name is unknown.

The architecture and construction of the tomb is astounding. The entire system is carved out of rock, with corridors just a smidge shorter than I am, meaning I have to bend my head to the side to walk down them. They are so precisely carved that the centre line deviates by no more than 5 mm.

This tomb is an important royal burial site, notably because Liú Zhù has been identified as its owner, through the discovery of his seal and dated coins. It has 15 different chambers; the one with his coffin is swamped by visitors, while his consort’s are sparse.

No doubt she was just as overshadowed in life.

We visit Yùzhào Bówùguǎn (the Imperial Edict Museum), which is the only museum in China dedicated primarily to imperial edicts. It is a beautiful building. We meet the founder and owner of the museum, Zhōu Qìngmíng, who welcomes us warmly and shakes each of our hands.

圣旨 (shèngzhǐ) = imperial edict (sacred decree)

The edicts, often written on silk or fine brocade, were official documents issued by emperors to grant titles, confer honours, or issue commands.

The calligraphy on some is impossibly fine.

I am drawn to the items that connect to the enduring culture of scholarship in China. The first is a large banner made of wood, once displayed at the home of the student who achieved first place in the examinations.

The second is a sheet of paper that folds into the palm of a hand yet, when unfolded, stretches wide enough to hold 200,000 characters.

A cheat sheet, if you will, for the imperial examinations

My wick starts burning low, so I’m relieved that our next activity takes place in a room lit with tea, art and music.

An elegant musician plays the gǔzhēng, as we sip our chrysanthemum tea.

古筝 (gǔzhēng) = guzheng (ancient zither)

We learn how to complete a tàpiàn, or rubbing. It reminds me of school days, shading the outline of a leaf through a sheet of paper.

This time, we are using stone tablets. The paper, strong enough to mould, yet fragile enough to split, is sprayed with a mist of water, then struck with a brush through a thin square of fabric.

A staff member assists me. ‘Like this,’ he says, smacking my fabric much harder with the brush.

The paper splits.

(It sure is tough to strike a balance.)

Paint is applied using a circular pad, which is gently patted across the paper. The colour adheres only to the raised sections, leaving the indentations white.

I love my impression, as much as I love how soothed I feel, having completed it.

The character it features means ‘sun’.

日 (rì) = sun