The Sūzhōu Sojourn

by afatpurplefig

We catch a bullet train to Sūzhōu. The journey of over 1200km takes a little over 五 (wǔ) hours. It is a welcome opportunity to sit, despite narrow seats designed for slighter frames. Attendants stride up and down the aisles, selling shuǐguǒ and delivering Starbucks kāfēi. Conall offers me a beef and coriander chip, which tastes exactly like beef soup. And I mean, exactly.

I read about radicals, the components of characters that provide contextual clues as to their meaning.

咖啡 (kāfēi) = coffee (phonetic transliterations both – aka KFC – each with a tiny (skinny!) 口 (mouth!) radical)

I find myself staring out at the landscape, trying to pinpoint why it looks so different. Eventually, I see it. The train moves through what feel like rural stretches, with great expanses of farmland. And yet, when I expect to see a sleepy country town, there are instead clusters of towering apartment buildings. It’s as though every train stop features a cityscape that wouldn’t be out of place downtown in an Australian capital city.

It’s challenging to take pictures from a train that moves so quickly. I like the streetlights of Tài’ān (pop. 5.5 million) enough to try.

In Sūzhōu, we have free time to explore Píng Jiāng Lù, an ancient lane that dates back almost 900 years, to Nán Sòng (the Southern Song Dynasty). It is all cobbles and lanterns and wanderers passing xiǎodiàn, selling trinkets and silks and nuò mǐ.

糯米 (nuò mǐ) = sticky rice (sticky rice)

(米 appears as both a character and a radical here. I will be keeping an eye out for this little rice star in future.)

I walk, at first alone, then joined by Conor. We see a harnessed māo with a legion of admirers, and a chained meerkat, straining. Conor buys himself a labubu (lafufu?) and a toy sniper rifle that is unlikely to last beyond our next security checkpoint.

‘I’m an adult now,‘ he says, ‘and I can buy whatever I want.“

With only minutes before our meeting time, I hear this voice, and lament not being able to sit there for a while, píjiǔ in hand. If I could, I would sway and hum and cheer, so the singer knows much he is appreciated.

啤酒 (píjiǔ) = beer (pí – phonetic transliteration (with a 口 radical), jiǔ – alcoholic drink)

I love the phonetic transliterations, this one chosen solely to represent the sound of ‘beer’.

Frances, our tour guide, is ready for us bright and early the next morning, irreverent humour at the ready. She begins by telling us about Sūzhōu, the ‘City of Rice and Fish’, and its canal system, which dates back over 2,500 years. It is the world’s largest artificial waterway.

Sūzhōu‘s official flower, Osmanthus, is a major feature of many of the city’s classical gardens. We can smell it in the air as we approach Shīzi Lín (Lion Grove Gardens). During his southern inspections, Qiánlóng Dì (the Qianlong Emperor) of the Qīng Cháo visited these gardens on five out of his six visits, which really put them on the map.

I decide to tackle every Hanzi character from this shop sign, as we wait to enter:

狮子 – lion

林 – forest

文 – culture

创 – to create

店 – I know this one!

The gardens, designed for meditation and contemplation, were built in 1342 during Yuán Cháo. There isn’t much meditation on the agenda today, with many a tourist on a quest to snap the perfect picture of a chrysanthemum, many of which are dotted throughout the garden.

I complete my own quest to snap an a-ok picture of a chrysanthemum.

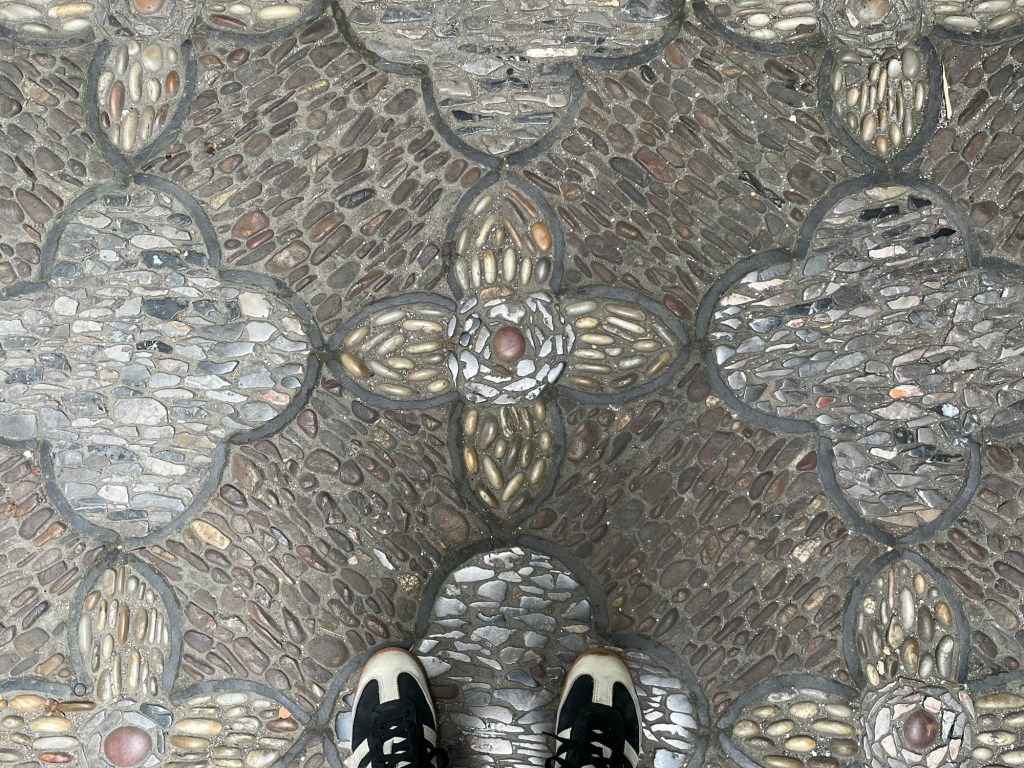

I find my own favourites here – stone tiling, photographic subjects, English translations on signs.

Listen-to-Waves Pavilion

Inquire-the-Plums Pavilion

Building of Creeping Fragrance and Thin Shadows

A highlight is seeing not one, but two recognisable characters on a sign, due to the already-locked in addition of 林. It’s hard to mistake the little duo of trees.

Later, we visit the Sūzhōu Museum, designed by I. M. Pei. It is a beautiful building, both modern and traditional, all at once.

I wander through the high-ceilinged spaces, past paintings and calligraphy, jade and ceramics, koi and pomegranate trees. I enjoy reading ‘To The Best Of My Ability’, by Yáng Fēiyún, the artist currently featured.

‘The primary function of art exists to satisfy the longing of the heart and the elevation of the spirit.’

I call this series of his paintings ‘I am Tired of Posing’. This isn’t meant to minimise his work, which is lovely.

I snap an ancient treasure and send it to Lula, who is drawn to archaeological markers of death, and try to contain the enormity of it all.

One of my favourite displays is this room, which reflects the style of furnishing favoured by Míng scholars. ‘Treatise on Superfluous Things’, written by Wén Zhènhēng, contains 12 volumes devoted to how to live. In the volume on indoor furnishings he states:

‘The furnishings shall better be antique than modern, better be simple than intricate, better be austere than vulgar.‘

Perhaps I am just craving a slice of calm.

We have extended free time in this space, but the crowds grow tough to contend with and the rain keeps me indoors. Eventually, I find myself a narrow section of stone wall upon which to perch, and while away the afternoon, listening to JJ Lin, and tappping out a post on my phone, painstakingly, with one finger.

All is still, but for a moment.

That building is incredible…I love the last picture 🙂