The KFC Solution

by afatpurplefig

Spotting recognisable Hànzì never gets old. Had the giant ‘P’ with a cross through it not appeared in this sign, I would still have known that this is an EXIT, and is not a good place to park. I’m not sure about the message on the left, but this I do know: it is a message about people.

These signs? Thrilling. I’m missing one character…one! I look it up as soon as is humanly possible.行 (xíng) = behaviour/conduct.

This means we have the following four characters:

行 = behaviour

人 = person

出 = exit

口 = mouth

Together: pedestrian exit.

It is a completely different way of thinking about language.

English and Mandarin are both spoken languages, but where English uses an alphabetic system, with each symbol representing a phoneme, or smallest unit of sound, Mandarin uses a logographic system, with each Chinese character representing a morpheme, or smallest unit of meaning.

And Mandarin is the only major modern language that primarily uses this system. Historically, there have been several (including the one everyone knows, Egyptian hieroglyphs), but Chinese characters are the only ones that have endured. In continuous use for over 3000 years, they represent the most widespread logographic system in human history.

And I really like them.

I find myself hoping for long bus rides, so I can play ‘Spot the Hànzì‘ without interruption.

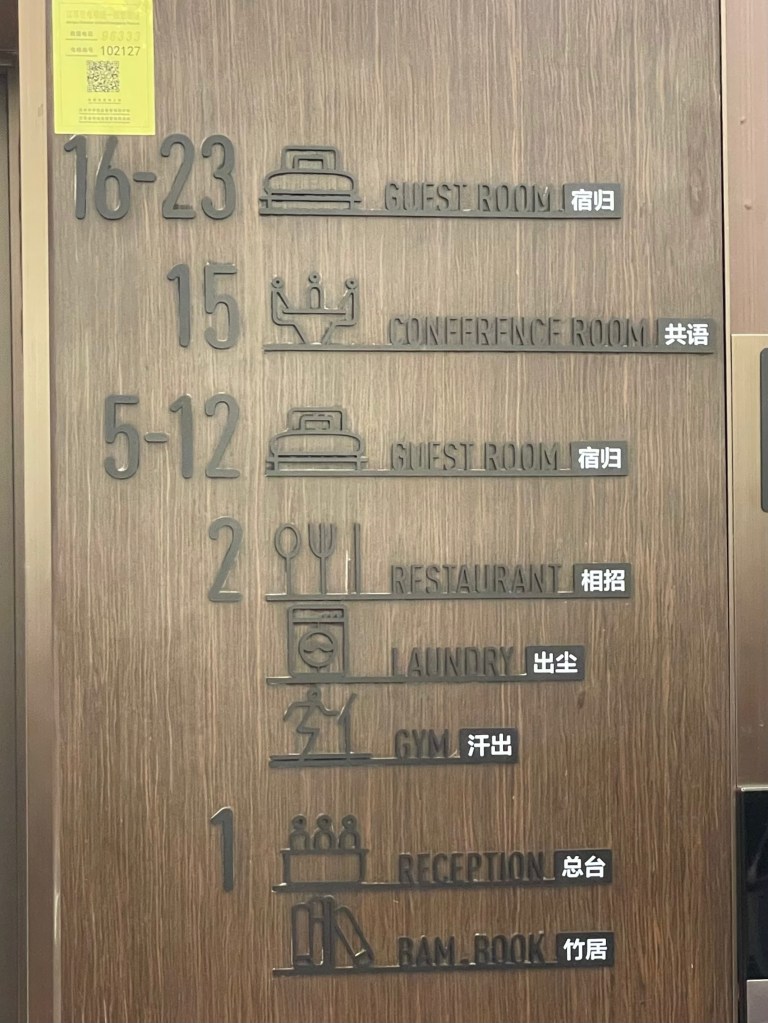

I particularly enjoy seeing characters I recognise, in a context I don’t understand. Look at the way 出 (exit) is used on this hotel facilities sign, for both the laundry and gym.

It turns out 出 is a versatile character whose meaning is related to ‘moving from inside to outside.’ So, in combination with 尘 (dust), we have ‘out dust’, and in combination with 汗 (sweat), we have ‘sweat out’.

These aren’t the typical names for a laundry and gym, mind you, but the fun titles the hotel has chosen. Imagine a laundry in Australia calling itself ‘Dustbusters’ and a gym called ‘Get Sweaty’ and you have the right idea.

(See how authoritative I sound? it took me ages to figure that out.)

Sometimes, a character used in an unfamiliar context leads me to a new word – a two-fer, if you will!

Case in point:

This one throws me, because I can’t see how the word 大 (big/grand) fits into our greeting. I soon discover that 大 combined with 学 (study) means ‘university’. And, as you might expect, 大 is used in plenty of two-fers:

大街 (dàjiē) = main street (‘big street’)

大海 (dàhǎi) = ocean (‘big sea’)

大门 (dàmén) = main entrance (‘big gate’)

You get the idea.

I think what I most enjoy is the creativity that lies at the heart of the characters. I am enamoured with 星期 (‘star period’ – week) and 手机 (‘hand machine’ – mobile phone) because of the imaginitive spirit in their construction. They are poetic metaphors.

And their discovery is a delight.

Until now, I have been using ChatGPT to identify characters, which has been the polar opposite of a delight. Take this exchange, where I am attempting to identify the character 大:

‘Which is the Hànzì that uses 人, but with a line across the top?’

The Hànzì you’re referring to is 人 (rén), which means “person” or “human.” The character is made up of two strokes: a vertical line and a small diagonal stroke, often seen as resembling a person standing.

‘No, this is a solid horizontal line across the top of the 人 character, forming a new character.’

Ah, I see! The character you’re describing sounds like 亻 (the “person radical”) with a solid horizontal line across the top. That would form the character 任 (rèn).

‘It is literally the character 人, but with a horizontal line crossing through the upper part of the 人 character.’

Ah, now I understand! You’re referring to the character 亻 with a horizontal line running through it, creating the character 仞 (rèn).

Maddening.

In Sū zhōu, I spot a keyring with a familiar character. ‘A single happiness!’ I think to myself, gleeful. I double-check with Conor, who deftly draws it into his ‘Pleco’ app.

‘It’s a surname. Dong,’ he announces, within seconds.

Sheesh.

On the bus, head leaning against the window, I spot something and am suddenly bolt upright. A KFC. How can letters be translated into a language with no letters? Perhaps they had to use the old name, ‘Kentucky Fried Chicken’.

The Chinese characters for KFC are 肯德基 (Kěndéjī). The meaning of the three characters is as follows:

肯 (kěn) = ‘willing’ or ‘to agree’

德 (dé) = ‘virtue’ or ‘moral’

基 (jī) = ‘foundation’ or ‘base’

It turns out that when there isn’t an existing representation for a word, characters are chosen for their combination of two things: phonetic resemblance and positive association. So, these characters don’t have anything to do with fried chicken. Instead, they emulate the sound of ‘Kentucky’ and imbue it with meaning.

KFC is unworthy of such a gift.

I am signing off today with the Chinese name chosen by my wonderful teacher, for which I have an enriched appreciation.

再见

白菲 (Bái Fēi)

It’s like every sign is a logic puzzle!

It is! Each translation becomes a rolling stone.